Custom kitchen cabinets, eh?

Perhaps as the next venture, instead of doing this incredibly complex software engineering and architecture combined with years of stress and poor sleep to get to products with high gross margins, I'll just start a panel cutting shop instead.

I started a kitchen renovation (remodelling) project some time ago with the goal of enjoying cooking great food even more by accommodating a steam oven and wok burner. Given my compulsion to experience new things and do things I've never done before, I decided to do the remodelling project by myself. A kitchen renovation is similar to the bathroom renovations I've done before and is generally grouped into a few phases: Demolishing what's there, rough work (plumbing and electrical), installing cabinets and appliances, lighting and flooring installation.

Kitchen cabinets are a large expense component for such remodels, often running to many tens or even a couple of hundred thousand dollars for large kitchens. Since I wasn't replacing all cabinetry, I needed the new cabinets to be stylistically consistent with the old ones while accommodating new appliances. I also chose to take advantage of a foot or two of extra space.

Ikea wouldn't cut it, due to the need to match what I have. No way around it - this was a "custom cabinet job" i.e. expensive. The lowest quote I got – for 9 ft of base cabinets and 3.5ft of hanging cabinets — was around $10,000. The next closest quote was $13,000 installed. This is the price of several heavily engineered premium laptops or the price of a second-hand car in great condition, and makes no sense. Are "custom cabinet shops" making a killing here? Let's find out!

Cabinetmaking vs cabinets

In the old days of woodworking gone by, a "cabinet maker" was a skilled trade. Craftsmen would build wardrobes, shelving units, chests of drawers, closets and all sorts of other items out of solid timber with floating panels, joined using hand-cut mortise-and-tenon or dovetail joinery and slick hardwood draw slides. This isn't what cabinet making means these days: Instead, we think of painted or stained boxes with flat fronts made out of MDF or plywood, manufactured hinges and slides, and a piece of stone on top. Custom has become code for expensive.

Realising how much plywood I needed and adding up the cost of screw-on hardware (handles, hinges and drawer slides) I SWAGged that I could do the job myself for under $2,000, resulting in a saving of around $8,000 compared to the cheapest quote. I posit that, in the San Francisco Bay Area, the "custom cabinet shops" are running with extraordinarily high gross margins, putting huge amounts of money in their pocket for what is mostly unskilled machine-based labour. There's definitely a business opportunity here!

How I built my cabinets

Making cabinets is actually a fairly basic process:

- Chop up the plywood sheets.

- Glue on edge banding.

- Screw them together.

- Install the hardware

- Make door fronts and install them.

- Make drawer boxes and fronts and install them.

The first thing to start with is a really accurate design. I did this on my laptop using Affinity Designer, but worst case, a pencil and graph paper would have done the job. It's important to think through the draw heights, widths, alignments, door opening directions, accommodations for the cabinet sides, toe kicks and everything else. I did this even before I approached the cabinet shops above, templating sizes off the already installed ones.

I'm lucky to have a decent amount of woodworking equipment at home. To make my cabinets, I used the following tools:

- Chopping: A track saw, track and vacuum for chopping up the plywood panels and a hand saw for cutting out the toe kick.

- Banding: A clothes iron and a roller for ironing on edge banding, and a chisel for trimming it.

- Joining: Lots of screws and an impact driver for most edges, and a Kreg jig for pocket screws used where sides are visible.

- Shaker doors: A router for cutting the grooves for floating panels and clamps for gluing them.

- A few miscellaneous tools such as a drill, a hand plane, a rag, sandpaper, paint, a paintbrush and roller.

Although at first inspection that seems like a long list of tools, I would have still come out ahead even if I had to buy them all from scratch and use them once for this project.

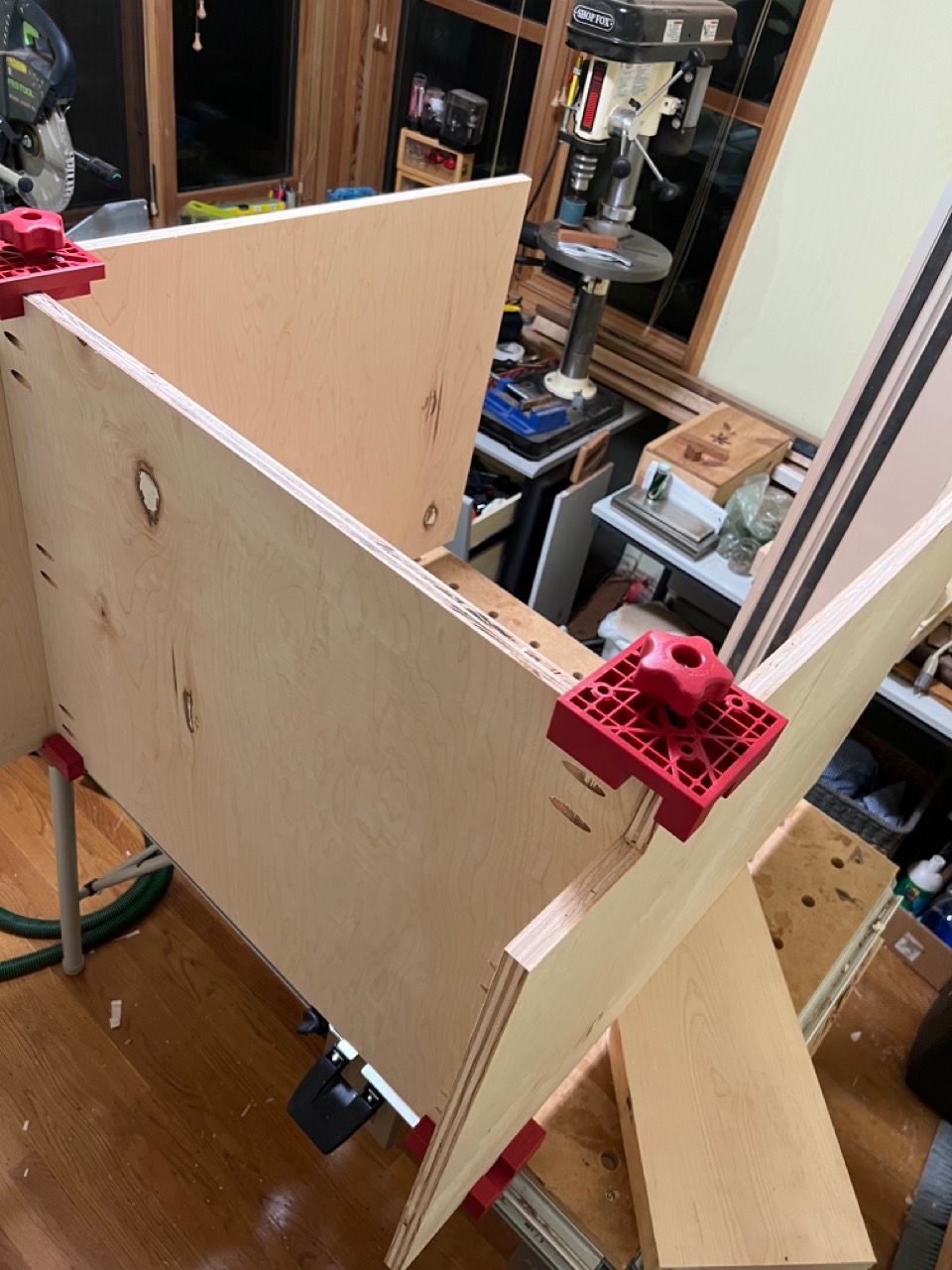

Some pictures from the construction are here:

Attention to detail and repetition

Building cabinets out of plywood is a lot easier than crafting furniture out of hardwood. However the single most important thing, which I find matters less when building things out of natural wood (where I like curves and natural shapes and live edges and things) is: Precision.

Your corners must be truly square. Which means your wood has to be measured really accurately. Under 0.5mm tolerance in cutting accuracy for decent sized panels. Otherwise, stuff won't line up well and when you extend the drawers, they will bang into each other chipping off paint. I've seen this in several cabinets made by a "custom cabinet shop" in my London flat: Try just pulling out all the drawers all the way, and see if the gaps are consistent. Your kitchen walls won't be that square, nor flat, and your floor won't be that level. So be prepared for shimming all over the place when installing, and always, always, always shim to keep the cabinets square, plumb and level. Any and all gaps can be filled by countertop, caulk and trim.

After that, it's seriously repetitious work: Chopping panels, ironing on edge banding, screwing, over and over and over again to build the carcass. For draw fronts and doors I used hard maple, so there was a bit of gluing, but afterwards, just more of the same. Drawer boxes? More of the same. Then varnishing, then I decided to paint it all instead. More repetition.

The (mostly) finished product

The finished product looks something like this. Note that it's missing stonework (countertop and backsplash) as well as a floor surface. However I'm pretty happy with how things turned out given the construction "on the cheap." Everything slides nicely, is properly aligned with consistent gaps, and things don't bang into each other at all when fully extended.

Cost estimate and how to scale this

I estimate that it cost me about $1,900 in materials to build these cabinets, purchased from big box stores (wood) and online (undermount soft close draw slides). Total labour was probably about 40 hours, including installation. At a respectable $50/hr pay rate — much higher than store and restaurant workers and the like – that's looking about $2,000 in labour. So these custom cabinets as made by the cheapest cabinet shop were running with a pretty substantial 61% margin. Now, they have costs like electric, rent for the workshop, replacing tool heads and whatnot, but that's offset by the far lower cost of materials purchased on bulk so overall one is still looking at a >50% margin which is pretty damn impressive.

However it gets better. Keeping tools set up for repeated cuts of known dimensions would have saved a ton of time. A spray shop to paint would have saved a ton of time. An edge bander would have saved time. Taking it even further, using a panel-sawing CNC machine would have saved even more time still, as would putting the labour in a much cheaper location for $20/hr instead.

When one looks at videos of the large cabinet shops in China and elsewhere like this one, "custom sized" pieces flow from machine to machine on flat bed conveyors requiring minimal human intervention.

It's clear that custom cabinet making can be scaled to become a very efficient business with very little labour involved by bulk purchasing materials, making extensive use of machinery for repetition and labour reduction, and running in a lower cost location. How, then, can custom cabinet shops demand such stratospherically high prices? Either they are substantially behind the times, or – more likely – just milking the market.

I think it's probably a combination of both. Suppliers in the San Francisco Bay Area have decent workshops set up for repetition, so can make things with far fewer man-hours than I can, but have also grown so used to big fat gross margins that they don't see a need to invest in more machinery or remote plants.

Perhaps as the next venture, instead of doing this incredibly complex software engineering and architecture combined with years of stress and poor sleep to get to products with high gross margins, I'll just start a panel cutting shop instead.