Making and drinking mezcal

I spent a couple of hours at the Jimenez Mendez distillery, chatting to the 5th Generation distiller. The distillery is in a small shack along the side of a road at the back of a family garden, but their spirits are amazing. The distillation process is described below along with photos.

Background

Mezcal is a drink that’s been growing in popularity in recent years. It’s made from the agave – a type of succulent – just like tequila, and some similarity in production technique but at the end of the day it's a rather different beast. Whereas all tequila has to come from a certain type of blue agave in Jalisco and is typically made in bulk using modern distilling techniques like stainless steel steam vessels and mechanical shredders, mezcal is made from many different types of agave using traditional manual methods. Production of the drink classified as ancestral mezcal is very much a local, regional, artisanal trade handed down through generations across nine different states. I was lucky enough explore the mountains and countryside around Santiago Matalan, near Oaxaca, to witness the production of this amazing drink directly. Given the large variation in flavours that can be obtained by distilling different varietals of agave and tweaking techniques, no wonder highly skilled bartenders all around the world are developing amazing drinks based on it, including the bar which to me is my personal global favourite, Coa in Hong Kong helmed by Jay Khan, recently ranked the best bar in Asia.

At Coa I’ve been lucky to explore tequilas, mezcals, pechugas (distilled with various fruits and meats above the copper still) and raicillas (the mezcal of Jalisco made with random local plants). To see how these spirits are produced is incredible: The ancestral producers make mezcal using nothing more than agave plants, a coa (a round blade on a handle used for chopping the agave), a fire pit in the ground, a horse or donkey, wooden barrels, a wood fire and a copper pot.

Production

I spent a couple of hours at the Jimenez Mendez distillery, chatting to the 5th Generation distiller. The distillery is in a small shack along the side of a road at the back of a family garden, but their spirits are amazing: They have even found their way to the US market, being re-marketed as the highly regarded El Buho mezcal by chef TJ Steele in New York City. The distillers were so patient to let us see the the whole process in its entirety, including sampling many mezcals some of which came straight out of the still during distillation!

The process, with some photos, is as follows:

(1) The agave is harvested. These succulents get really big, 7ft wide or more, and for mezcal the plants want to be at least 7 years old. The leaves aren’t used and are chopped off, it’s the core of the plant, the piña, which is partly below the ground that we’re after. The agave is harvested with a coa, a type of hoe with a sharp round blade on it.

(2) The agave piñas are roasted in a rocky fire pit with a combination of woods known to the distiller, and covered. The agave can roast for several days days, helping to extract the sugars, sweeten the plan and imparting some of the signature smokiness.

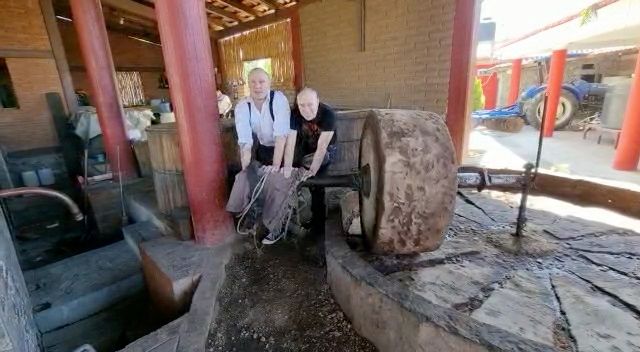

(3) The agave is chopped up, thrown into a stone pit with a giant, heavy wheel above, and mashed by the wheel moving round and round. The solid stone wheel is incredibly heavy; it takes two full men to push it, even with no agave present. With agave present, moving the wheel around requires more horsepower than humans can offer, by means of literally using a horse or donkey. It's not uncommon to see a lot of donkeys and horses roaming around the mountains and this is why!

(4) The mashed agave is placed in a wooden barrel with an open top, warm locally sourced water is added, and the mash is left to start fermenting. In this case, no special additives or yeast are present; it all happens based on what’s in the agave and naturally in the air, on the plant, in the hair of the donkey, around the barrel and generally nearby. Water is added again, leaving from 1-4 weeks depending on temperature and humidity until the colour starts to turn dark on top at which point the mash is ready.

(5) The thick mash, fibre and all, is loaded directly into a copper still and heated by a wooden fire underneath. The mezcal is captured at the end of the still in a large concrete pot or bucket.

(6) The good distillate in the middle of the concrete vessel or bucket is then distilled a second time. At this point the ABV is a bit high, so some water is added to the mezcal - which to temper it down to the expected range.

Types of agave

There are many types of agave that can be used to produce mezcal. The dominant varietal is Espadin which accounts for 80%-90% of all production. At the distiller, we also tried Tobala, Pulquero and Jabali. Upon trying many types, we found that actually the Jabali was preferred by the group, followed by Tobala. Jabali had a more subtle, deeper flavour with more dimensions perhaps more reminiscent of Scottish whisky. We even tried a particularly interesting variant that had a marijuana plant added to the final bottle!

Some final thoughts

During the process, people who lived nearby would come to the distillery carrying plastic water bottles to stock up on mezcal direct from the producer and enjoy with their families.

Upon bringing a couple of bottles back to California and drinking the “real deal,” both my friends and I found that the mezcal I'd accumulated at home - from spirit shops in the US, UK and even Mexico, as well as duty free stores and markets – were of such comparatively poor quality that they just didn't make the grade and tasted quite horrible alongside. If you think mezcal tastes bad, it’s because you’ve never tried the good stuff, which is the case with tequilas, whisky and most other spirits as well.

At the end of the day, each and every ancestral mezcal is made by families using different varieties of agave grown in different areas, roasted in different ways with different types of wood, fermented using local yeast and local water using different timings and methods and vessels, all during different seasons and climates. These variations lead to a vast variety of spirits waiting to be discovered. Mezcal's so different from mass-produced tequila, in a good way.

I highly recommend visiting the Oaxaca region not just for the day of the dead celebrations, not just for the amazing food and moles, not just for the beautiful surrounding countryside, not just for the history, not just for the friendly people, but also to try the hundreds of types of local mezcals. There are many mezcaleria bars in the city serving hundreds of types of high quality local mezcals at reasonable prices. It’s so much more of a cottage industry than the production of whisky or bourbon and there’s a whole world of tastes waiting to be discovered.